The summer I turned 22, I could finally appreciate the sentiment that underscored those mushy Hallmark platitudes. James had turned eight in the spring—just under 50 in cat years—and I loved him dearly. But I’d never forget when Edith came to me, jet black and demure as she seldom spoke; and when she did, she tended to whisper. Her voice remains one of the things that sets her apart from the others. First, from James whose tone was always intent and incisive. Later, Vera who had a voice that was distinctly dysphonic: raspy and mangled but bang on with its pitch. Then, Clark whose reserve and indecision distend even the most casual calls into wails. Even today, I still can’t quite explain it. All I know is that when we first met, Edith intoned a curious albeit honest endearment that etched into my heart forever. The fact that she speaks sparingly prompts me to acknowledge her whenever she does. Although I’m told that cats—like people—tend to talk more as they age, I still find myself keen to address what have become frequent utterances.

Like the others, Edith shares a namesake with one of my late relatives: my maternal grandmother, nicknamed ‘Ada,’ who was a devout optimist. I’m grateful for the time we shared since she succumbed to cancer when I turned eight. She proved to be somewhat of an anomaly, attributed to palliative care indefinitely and resolved—and largely, successful in her efforts—to be active. Her children remember her as selfless; raising them independently after my grandfather was lost to cancer many years prior, often foregoing her own intake and leisure to ensure theirs. They tell me that she often said things to me which seemed macabre, but I recall these things to be maudlin in hindsight. Aware of her ailments, she would tell me goodbyes. “I’m going to leave,” she said. “I’ll be here, but you won’t see me.” Several times, she emptied her purse to gift me the entirety of its contents, assuring me that they were better in my hands since her ‘departure’ meant these were things she’d no longer need.

Upon reflection, I think the loss of Ada defines why I still find death hard to come to grips with. I likewise find myself viscerally averse to any type of ‘departure’ from my life, even as I recognize people have the prerogative to abandon me beyond the context of mortality. This has fostered my tendency to mourn the people, places, things that are currently in my life to which bereavement overshadows them. I struggle to live in the moment because I find myself disassociating from it, knowing that the moment will inevitably pass. Even now, as I feel blessed to have Edith for 14 years—to which she’s roughly into her early 70s in cat years—I also feel sad in knowing she too will pass.

Like James.

Like Vera.

And Clark will pass too.

Everyone will.

Which is odd since I think I’m somewhat more amenable to that than the prospect of them leaving, living without me on their own accord. Surely, this betrays some pride or narcissism on my part, but this sentiment is hardly unique. The aftermath of any departure—a breakup, ghosting, abandonment, and so forth—embitters those left behind. It hurts whether we possess the wherewithal to be accountable for what parts we might have played in that exit, or acknowledge what toxicity underscored those who would choose to leave us as if we were expendable, or just accept that people are well within their rights to unravel our grasps upon them. Over the course of our lives, most of us learn—and nurse—that pain firsthand. Consequently, this pain defines us. Not in the sense that life is exclusively pain, but in that we cultivate the skills to push past this and muster the gumption to live life nonetheless.

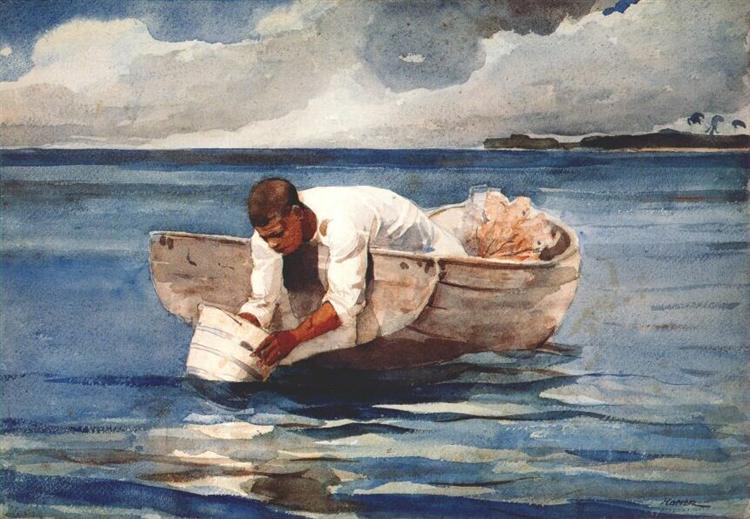

But as Edith comes to purr at my side, these days, life as I know it has come down to outliving those I care for and staying after others have left. I think back to the summer we met: when her undertones complemented what reeds whispered and swayed in the breeze; and she would burrow her small face into the crook of my arm, then her pupils would recede to slits as we watched the sunset cast fiery hues across the horizon. Back then, I thought back to Ada who resolved to do wash clothes by hand since she believed laundry appliances were insufficient. I remembered being a kid, carting soap to her pail, helping her peg each garment to the clothesline to later retrieve the dried colours and textures that would dance in the wind.

It seems almost eerie that Justice League: The Flashpoint Paradox (2013) debuted shortly after I first got Edith; and I say ‘eerie’ because the moral quandaries posed by time travel and prospects of quantum physics now endow me with a sense of relief. Like, this idea that all things—including the bad things—are fated to happen to oblige a grand [existential] design and we should neither rue nor alter them lest we jeopardize the fabric of space and time. Which encompasses the premise of The Flashpoint Paradox: the Barry Allen iteration of The Flash (voiced by Justin Chambers) travels back in time to prevent his mother, Nora (Grey DeLisle), from being murdered therein yielding an alternative universe and timeline. However, he lacks his powers in this reality. Barry also discovers his wife, Iris (Jennifer Hale), is married to someone else and the Justice League ceases to exist. This reality is on the brink of a world war, caught between the misanthropic Amazons led by Wonder Woman (Vanessa Marshall) and the speciesism that informs Aquaman (Cary Elwes) whose legions declare “land-dwellers” to be a scourge. In oversight, the powers that be duly conclude that contemporary society will be caught in the crossfire as the onslaughts foreshadow mutually assured destruction.

While Cyborg (Michael B. Jordan) has grown to become a government operative who the Shazam family aid, the Batman and Joker personas are assumed by Thomas and (Kevin McKidd) Martha Wayne (also Grey DeLisle) respectively while Bruce was the casualty of the fated encounter in Crime Alley. Hal Jordan (Nathan Fillion), although a decorated pilot, never becomes the Green Lantern. Martian Manhunter has also failed to materialize. Superman (Sam Daly) is later found to be imprisoned by the American government, neither utilizing nor realizing his powers. There are several other heroes and villains—Deathstroke (Ron Perlman), Lex Luthor (Steve Blum), Captain Atom (Lex Lang), Steve Trevor (James Patrick Stuart), Lois Lane (Dana Delany)—who assume covert operations to no avail. With Thomas’ help, Barry recreates the accident—being struck by lightning and drenched in forensic chemicals—that gave him his powers. While the first effort leaves Barry badly burnt, the second attempt succeeds to restore his powers.

But all is for naught.

In their quest to best one another, Wonder Woman and Aquaman have devastated the citizenry wherein they’ve overridden legal order and razed countless nations. Everyone who comprises resistance efforts—alien, metahuman, mortals alike—are killed. After Wonder Woman bests him on the frontlines, Aquaman refuses to concede and so detonates a nuclear bomb his forces have engineered using Captain Atom.

Armageddon ensues.

Barry notes that his initial time travel was possible because, during, his nemesis The Reverse Flash—Eobard Thawne (C. Thomas Howell)—was not simultaneously using the Speed Force. Conversely, in this timeline, Eobard now uses such—which means Barry lacks the power to time travel.

Beyond the fray, Eobard emerges to reveal that Barry is to blame for this timeline, explaining that Barry fractured spacetime by traveling to the past to save his mother. Gloating, Eobard pummels Barry until he’s fatally shot by Thomas. With Eobard dead, Thomas implores Barry to use the Speed Force—now, free from Eobard—to travel back in time: “The only way to save the world is to keep this world from ever happening.”

So, Barry runs and confronts himself along the way, preventing himself from intervening in the literal event of his mother’s murder. He later awakens to discover his original timeline restored wherein he is The Flash and comprises Justice League. Iris is shown to be his wife again, by his side at Nora’s grave, and he gleans some relief in that his actions yielded this outcome. Afterward, he visits Bruce Wayne (Kevin Conroy)—the Batman of this time—to ponder the experience; musing on the fact that he retains the memories of his alternate self—joys, special occasions, milestones—that ensued with Nora in the other timeline. Bruce speculates these memories could be a gift of fate, affording Barry a small mercy of recollection given his tragic loss—to which Barry gifts Bruce a letter from Thomas.

When Barry delivers Thomas’ letter, I think of the astronomical depth contained in that message; the weight those words must’ve carried across time. It’s nascent of our proclivities for people we’ve never met, places we’ve never been, or styles we never lived to model.

Kinda like how I love disco even though I’m a millennial.

When disco emerged in the 1970s, it transcribed a fusion of themes and cultural movements, integrating the festive and contentious aspects of its time. The core of disco is freedom, escape, and inclusivity. The genre historically offered a vibrant counterpoint to sociopolitical turmoil of the era like the Vietnam War, stagflation, along with calls to action which hailed from [Civil, gay, feminist] rights and other countercultural movements. Empowering BIPOC and LGBTQIA2S+ remained at the forefront for social change as this period was marked successions—newer waves—of initiatives for rights and inclusion that preceded them. For belaboured communities, disco served as a refuge of upbeat tempo, infectious rhythms, and [typically] glamorous lyrics that encouraged dancing and joy; which resisted conservatism and repression.

Of course, Saturday Night Fever (1977) would mark its decline. The film launched disco to unprecedented heights of mainstream popularity, transforming the genre—created and centered around marginalized positionalities—into a global commercial phenomenon that saw disco oversaturate markets. This would account for the deluge of disco records and themed products, noted for their subpar quality, that endeavoured to resonate less and maximize profit. All of this underscored a public fatigue as masses started to liken disco as formulaic, insipid, and sensationalized. Which would culminate in the ‘Disco Sucks’ trend that prompted a riot that overtook a stadium in which they set a pyre of disco records ablaze.

Still, the eminence of disco is timeless. Which is why I find it resonant even though I didn’t live through its peak. In their respective plights and objectives, Eobard and Barry impart this through their time travel, conveying that transcend their historical contexts for anyone, any place—any time—derive new meanings and respects. While The Flashpoint Paradox follows Barry and the accursed inhabitants of the alternate timeline, Eobard Thawne is at the centre of the narrative’s dynamics. His manipulation—exemplified in replacing Barry’s costume with his own, taunts, and blows—serve to affirm his omnipotence within the storyline. Both Batmans undermine Eobard as a narcissist and sociopath. I still doubt either of them could’ve foreseen the lengths he’d go—or rather, run—to quench his harrowing contempt.

Even as Eobard declares that Barry is to blame for the doomed alternate timeline, he says it’s “worth it” should he himself perish in the catastrophe. The revelation that Barry’s own actions created the Flashpoint timeline—despite Eobard’s provocations—illustrates the interplay between villain and hero, wherein Eobard’s influence transcends mere physicality and delves into the psychological, even existential. Eobard’s ability to manipulate time, survive paradoxical shifts, and maintain his influence over events and [Barry’s] psyche, enshrines him as a central figure whose significance in the narrative is as profound as it is unsettling, emphasizing his power and the focus on his character even as the story follows The Flash.

The Flashpoint Paradox also marks C. Thomas Howell’s voice acting debut, and he absolutely knocks the characterization of Eobard out of the park. Eobard is driven primarily by personal vendetta. What defines him are envy, hatred, and a desire to prove himself superior whilst knowing his pursuits adversely affect spacetime. His objectives don’t align with broader ethical principles. Rather, they are fundamentally selfish and destructive wherein his time alteration holds consequences which extend far beyond his personal antagonisms. Eobard is not only cognizant of the fact his actions threaten universal stability in addition to countless people and timelines; he also relishes the broader implications of his pursuits which are rooted in personal animosity and a desire to subjugate or destroy despite collateral damage. However, this perspective is underscored by an obsessive refusal to accept any outcome that does not align with his desires. In 2010, Geoff Johns illustrates this excellently in The Flash: Rebirth where we see Eobard going back in time over and over again, striving to engineer his own favourable outcomes, only to grow increasingly miserable because he finds himself yielding the very same—and worse—outcomes that he sought to amend.

What makes Eobard so relatable is his inability to accept the things he can’t change and that he himself refuses to change. This underscores a universal truth about the futility of trying to achieve happiness or growth through harm, and the detriment of refusing to accept and adapt to life’s inherent limitations. For all his powers and ingenuity, Eobard is ultimately characterized by a lack of empathy and an objection to grow or learn from his experiences. Which is why he pairs well as a nemesis for Barry whose indomitable will is conversely shown to be a source of strength and resilience purposed for a greater good, whereas Eobard’s resolve begets anguished actions and outcomes which speak to his maladjustment and failure to constructively engage with the challenges of life. There may be elements within him that aspire to overcome adversity, but what takes precedence is a commitment to impose his will. His animosity with Barry imparts a broader theme that the nature of one’s will—whether it is used for growth and positive change or for selfish ends—plays a crucial role in defining heroism or villainy.

And Eobard’s motifs go beyond obsession. He’s so preoccupied with power, control, and altering reality that he neglects the importance of personal fulfillment, interpersonality, and goodwill. His happiness is contingent on the affirmations of others and systems, which is a precarious and hollow premise for one’s value. Eobard embodies what becomes of those who become more entrenched in their ways through ignobility and manipulation for which individuals who fixate on their pasts grow alienated, bitter, and trapped in a cycle of despair wherein they never truly “win” or heal. Another element to Eobard: his inability to grasp that the essence of life is change; and I think that inability is derived from the fact that he exists as a paradox in time, impervious to change. Other films and comics provide this insight as Eobard was actually running through time opposite Barry. Therefore, he was unaffected because history changed therein. These changes occurred when he was outside of history and as such, he did not comprise it. He lacks a marked beginning and end. He’s a paradox because, by this logic, he shouldn’t exist.

Ironically, only after Edith had curled into my lap, this was something I could make sense of. Eobard exists like Schrödinger’s cat. And ICYMI: Schrödinger’s cat is a thought experiment in quantum mechanics that illustrates the concept of superposition—where, until observed, a system can exist in multiple states simultaneously. When applied to Thawne, this analogy speaks to his likeness as a paradox. Since he lacks a history, he comprises all states of being in unison. He can’t truly die because there’s no point of reference wherein he lived; and he can’t exactly be alive since he transcends the concept of life itself. Eobard is simultaneously erased and intact across different timelines. This duality allows him to exist in a state of quantum superposition, present and not present in the continuum of spacetime. He is alive exclusively in a narrative sense, acknowledged by those external to him. His impact is only real if observable by others, even though his origin point or historical continuity is not fixed. This puts his ignorance to internalizing a peace of mind into perspective; and draws an interesting parallel for us as we exist inasmuch the eyes of our beholders.

This is punctuated by the fact that, in hindsight, Eobard is the one who spurs Barry to time travel. The former taunts the latter: “Enjoy your petty little victories, Flash. But no matter how fast you run, you can’t save everyone. Not the ones that matter to you.” While this taunt inclines Barry to go back in time to save Nora, invoking the grief that haunts him since childhood, it also resonates with a desire to prove Eobard wrong and alter his fate for the better. But save for his costume, Eobard is hardly seen for most of the film which serves to foreground the chain of events that define the complex moral and ethical dilemmas associated with time travel and the butterfly effect. And when Eobard does emerge, he calls Barry out, affirming that this doomed timeline is quite literally the hell to pay for interference. When Barry alters time to suit his own ends, he treats time as a vanity project. “You didn’t stop JFK from getting assassinated or make sure Hitler stayed in art school,” Eobard chides, “You saved your mommy. You missed her.” While Eobard merely goaded Barry, it’s the latter whose actions have wrought Armageddon.

Which ties back to the [Serenity] prayer that Nora imparts to Barry as a child, recalling her own grandmother telling her the same: “Accept the things you cannot change. Have the courage to change the things you can. And have the wisdom to know the difference.” This prayer raises the question of discernment in human agency: how we distinguish between what is within our power to change and what is not, considering the limits of our control and influence. It begs the question of not only how we reflect in terms of acceptance and action, but also in how we apply wisdom to our lives. In The Flashpoint Paradox, this is thematic in that even those empowered—whether superpowered or respective to a privileged positionality—must concede to inherent limitations because there are certain aspects of life and reality that we simply cannot change. The advice also affirms the importance of having the courage to change the things that are within one’s power—which kinda reminds me of Spider-Man as I think of my own elders when remembering how Uncle Ben famously said, “With great power comes great responsibility.”

Elders who loved me, who ultimately wanted nothing more than for me to grow into a good person; a kind, loving, and selfless person who would do the right thing with whatever power I have. They believed in me—my goodwill, pride, and all—and supported my dream of [permanent] professorship so as to be empowered within academia which would translate beyond. If you have the power to do good in this world, you have a responsibility to do that good. That also means accepting when you fail to do so; whether that’s all the time you wasted trying to find happiness in people who fail to see you, or all the love lost between yourself and beloveds, or the demise of those you loved because you refused this responsibility.

Because people seldom recognize and undertake the truth of who (or what) they are or have become.

And, some wistful part of me wants to believe that it was no accident that Edith’s advent coincided with this insight. As I hold her in my arms now, I’ve yet to let go of the fears I held back then. Which is ironic as most tend to hold me in high regard, yet never think twice to let me go. Most laud me as strong: a scholar who’s fast-tracked several degrees, working my fingers to the bone with several bones to pick with those who fail to appreciate my efforts; whose lectures impart competence and charisma; whose words decorate peer-reviewed and non-refereed publications.

Except that’s not the whole truth.

As a lonely, cynical workaholic, I’ve internalized that I’m powerless and expendable; that I’m doomed to squander what scant power I possess. My pursuits evince as much resolve as desperation because I refuse to concede to limitations and strive to act decisively where I can make a difference. I’m alright with the how, why, who, what, and where.

What gets me is the when.

It’s not that I regret my mistakes in and of themselves. I regret making them in the first place.

But this isn’t unique to me. The desire to travel back in time [to correct past mistakes or avoid pain] encapsulates a fundamental aspect of the human condition: our capacity to reflect and for shame. This longing stems from our ability to contemplate our actions and their outcomes, coupled with an intrinsic wish to alter decisions that led to negative consequences. It attests to understanding causality and how subtleties impact life as we know it.

At the same time (no pun intended), it evokes antithetical desires: the want to learn from our experiences, whilst wanting to negate what pain or loss accompanies these lessons. These desires belabour our efforts to live an ideal life of happiness as we strive to minimize our suffering and avoid loss. They personify our psyches through aversions to pain and capacities for care. When I yearn to go back—to prevent myself from acting in certain ways, being in certain places, meeting certain people—it’s not because I want a personal do-over. It’s because I broadly aspire for perfection and protection for myself and those I care about.

So, I repine what is as I dream of what could be.

My parents would probably be happier if I didn’t exist. To call them estranged would be an understatement. Without me, they wouldn’t be obliged to cross each other. My absence would proffer them the freedom to pursue their happiness independently, so it’s conceivable that their lives may be better without me in them.

Likewise, my siblings would be better off. My sister would be more favoured. We’re seven years apart, so I can only imagine how better established or aware my parents would’ve been had they met and conceived then—as opposed to prior with me—at that juncture of their lives. They could’ve given her more acclaim for lack of comparison. The same also goes for my late brother. If I was never born, my parents could’ve devoted themselves—more time, attention, and resources—to him. Maybe then, they could’ve ascertained and subsequently intervened to rid him of his inner demons; instead of fruitlessly pouring into me since my gainful employment or benefits have yet to—if at all—materialize.

Come to think of it, my partner might be content if we never met. I cannot begin fathom how he tolerates my flaws. An assortment of obsessive compulsions and anxiety mark my own struggle to even stand myself, so I can only imagine how burdensome someone else would find my insecurities. Given our own proclivities for isolation and resignation to our fates [which seem contingent on obliging others to our own detriments], I wonder if our connection ensued as a consequence of a misguided time traveller.

On the other hand, my counsellors argue that my non-existence wouldn’t necessarily ensure these positive outcomes. Seemingly random or chaotic states of systems can arise from underlying patterns and deterministic laws, challenging traditional notions of predictability and control. Chaos theory, with its emphasis on the sensitivity of systems to initial conditions, provides a fascinating grounds for this; and is also a lens through which we might view the attempts of Eobard Thawne and Barry Allen who travel time to find fulfillment or happiness. It suggests that even minor changes to the past can lead to unpredictable—often vastly different—outcomes, rendering time alteration [to any extent] risky. This problematizes time travel because its uncertainty is not guaranteed to result in favourable outcomes. Less people are familiar with chaos theory than its famed butterfly effect, positing that even the smallest change causes profound impact.

For Eobard and Barry, chaos theory notes their attempts to manipulate are fraught with potentials to spawn incidental effects which are far removed from their original intentions and desires. This resonates in several of their story arcs where their attempts to alter the timeline cause collateral damage, complications, or further personal and moral dilemmas. As such, their stories often impart that the pursuit of happiness—especially using such drastic measures as time travel—overlooks the immanent caprices of complex systems, like human lives and societies. Additionally, personae and viewers alike come to the same realization: no matter the time or place, or intervention, inequities and disparities persist. Eobard grows bitter, entrenched in recurrent letdowns, to which he absconds goodwill, citing the absence of guarantees. For Barry, in contrast, the Serenity Prayer is practical wisdom to face—and respect—the interplay between order and chaos. As for me, my non-existence doesn’t negate what abject prospects my parents, siblings, and partner could face. My parents may have ended up with different [worser] partners. My siblings could’ve succumbed to darker forms of anguish. My partner might’ve fallen prey to a fatal attraction. These dismal potentials should therefore merit my existential value.

But they don’t.

These alternate “worse” scenarios denote less truth than pathos. Optimistic platitudes elicit irritation rather than comfort. To put it mildly, there’s a massive gap between these prospectively “worse” timelines and how my pessimism is affirmed in this one. I need concrete solutions and assurances, not rhetorical devices. Do people still think knowing “it could be worse” does anything to allay despair or anxiety? Do catharses ensue when we’re aware of grosser alternatives?

The reason I identify more with Eobard comes from another paradox of [good] morality and material prosperity. Barry allows his mother to be murdered as ordained in the original timeline to spare the other one, which imparts we ourselves must suffer the bad to befit a greater good. But for marginalized peoples—historically enslaved, assimilated, genocided peoples—this doesn’t land. It is sheer fallacy to purport we must suffer to spare others given our peoples’ erasure and exploitation, especially when the “greater good” functions as a supremacist worldview that is hegemonized. To that end, morality has been—and continues to be—instrumentalized by privileged positionalities whom are empowered as gatekeepers as well as within stations of allocation and oversight. If I were to concede to hope—premised on an idea of a world whose atrocity justifies the reality of this one—I’d be lying to myself. These platitudes feel fake, engineered to quash any resistance and ensure complacency.

Which draws me back to Edith: I remember when she first met James, how earnest she was to keep her distance. I remember how long it took for them to finally get along, weeks later, and being mindful of the fact that my desire for their camaraderie neither obliged nor guaranteed them to get along. As I supervised their exchanges, I mused upon how, just because I chose them, that didn’t mean they must follow suit. These days, Edith kneads when I find myself enraged by people who insist everyone else must write themselves towards their desires. People for whom, outside of their wants, we cease to exist; people who shrug as we perish, but volunteer to deliver our eulogies; people who insist suffering makes us better, yet are agonized when their karma takes shape in grievances. We’ve all met them. Maybe once, we were them; but that doesn’t make us bad people. Because good people change. All the same, as much I try to be a good person, I don’t flatter myself. While people from several walks of life call me “distinguished,” I’m far from perfect. Like you, I struggle to make life work and to persevere against bad odds which feel insurmountable. Every decision I make comes with new problems to deal with.

How many times have you asked yourself, “What am I supposed to do?”

I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. I just know what I’d like to do, and I try to be mindful of that distinction. While I can’t time travel, my ancestry has made me privy to historical and ongoing atrocities of the charred aftermaths of lynchings, frozen cadavers, and peals of agony. While these profoundly unnerve me, they’ve been glossed over or commodified by token wealthies, hypocrites, and charlatans—all of which conspire to cheat and demoralize me. I don’t have a morsel of their power, so my truth cannot overcome their falsehoods. I can’t relate to Barry because I don’t see any “greater good.” Like, how entitled is it to deprive me even more in the interests of a status quo wherein good itself [as is] can’t be salvaged? Like Eobard, I’m inclined to be amoral since the prevalence of injustices vindicate my cynical worldview. I’d gladly perish in an alternate timeline where I was assured acceptance, purpose, happiness—even if only for a short time—to spare myself further anguish and indignities I’ll likely encounter (or cause) at this time.

I don’t choose to be a pessimist. I just can’t help it.

What sets me apart from Eobard is people.

Recent versions of Eobard cast him as somewhat of a victim when foes murder one of his ancestors, thereby eliminating his home [the future] and confining him to the present. Although this narrative isn’t definitive, it draws upon the sense of rage and displacement inherent to his character. Eobard was isolated and disconnected from everyone, everything, long before he became unmoored from time. Eobard becomes a super-speedster through replicating accident that empowered Barry because he idolized him; and this idolatry is augmented by the absence of Eobard’s own sense of purpose and meaningful relationships. Their fated enmity comes to pass when Eobard snaps once he uncovers records which identify him as Barry’s nemesis.

As much as Eobard wants to emulate or best Barry, what he truly ultimately wants is fulfillment. His ends aren’t justified, only occluded by his extraordinary means. Moreover, Eobard is shown to deceive any and all allies. It occurs to me that Eobard doesn’t choose to be disloyal, but rather he can’t help it. He betrays others, even himself, because everything he does betrays an underlying sense of not belonging. His choices are informed by a desire to matter and be remembered—which betrays that he is so removed from humanity, striving to connect by manipulating time, only to further alienate himself. Eobard is thus truly tragic, the epitome of how the pursuit of power to supplant identity ensures antipathy.

Which parallels how my own pessimism—defined by my disempowerment—renders me perpetually at odds with the world and myself. Instead of adaptation or acceptance, vengeance seems to be a more apt objective for the injustices, inequities, and such that I’m subjected to. I want to get back at the iniquitous—former advisers, mentors, and grifters—who told [and continue to tell] me my thankless, tireless drudgery would assure worthwhile, if just good outcomes. I want to reclaim a future I was denied, a glowing future that was promised to comprise my present. My timeline is literally up in the air because colonial regimes have murdered and cheated my ancestors; and I’m now told to “make do” by folks who came by their intergenerational wealth and cultivated assets off the backs of my peoples’ erasure, enslavement, and extinction. And even after I oblige and surpass ascriptions of merit, I’m still denied. But those in oversight are in my ear, imploring me to “enjoy the journey” as I lament the future being unclear. This too is not unlike Eobard who, rather than accept and adapt to signs of the times, desires to avenge his lost futures, making his rage and displacement a natural, if destructive, path for him.

This is the irony of Eobard, exempt from the conditions of spacetime but remit to past grievances; a living paradox who lives outside of time only to define himself within it. Even now, I get teary as I look to Edith, in spite of her good health, pondering her inevitable departure. I could never forget her; I wouldn’t want to. Just like Ada. Yet, I can’t reckon with the finality of loss. That is, I strive so deeply to gain in an effort to negate my losses. Eobard similarly acts not so much in the interest of winning, but to appease his aversion to responsibility. Where, when, and how he runs indicts his attempts to run away from the pain [and accountability] associated with acceptance.

But I actually have people I care about, the same people whose lives I [ironically] wager my non-existence would benefit. They impart the value in facing the truth. The whole truth. Life is so vast. It can’t be consigned to gratuitous evils. There’s truth in that my family manages to chip away at my heart; and I hope that my partner, in his heart of hearts, resolves to hang in there for the truths our love evince. Truth is what moors fear when you share your heart with someone. Specifically, the fear that expressing your truth is too much for your beloveds to bear. It’s hard. But this feat leads us to find—and feel—something greater, something more. Truth doesn’t undo us. It makes us stronger. Even though it takes time, even knowing that there may be more to overcome, your truth resonates with you more than what precedes it.

This was only something I came to realize after meeting my partner. For my tendency to make mountains out of molehills, what tides me over is knowing he isn’t subject to the [grim] whims of my imagination (although I still wouldn’t be surprised if a time traveller appeared and admitted they had a hand in things). Truth taught me to hold on, if only for a second longer. Although I wonder if those who’ve passed learned this, I can only wish them well, wherever they are; even alive and well somewhere else in time, and I can only respect what suffering I needed to feel, if only to assure their wellness.

My mind wanders to alternate timelines where I can simultaneously exist and observe my non-existence.

I think of encountering my parents, both of whom radiate confidence and contentment, pausing as they’re struck by déjà vu as I hold a door open for them in passing. They might be together, they might not. In any case, they’d have more colour in their cheeks.

My mother wouldn’t be as tired. She would muster the energy to take charge, take stock of her ambitions, totally free to indulge her dreams and leisures since my absence would afford her more time and resources. And she wouldn’t consider the consequences for talking reckless. “Next time is next time,” she’d scoff. “Now is now.”

My father would appear less wan and sound less hoarse. He wouldn’t think twice to regale anyone with his tales of memories, because he’d have so much more without me there to weigh him down. Even if I revealed who I was, I wouldn’t be surprised if he still reiterated what he often tells me; about how we can only go forward and learn to navigate our wants and abilities within the larger framework of what is right and possible.

My siblings would exchange looks after they caught sight of me, slurping an XL soda, when they make a pit stop for one of their road trips. Maybe my brother would replace his cap, shifting his weight from foot to foot, and derision would subsume my sister’s curiosity. Either one of them would remark on how they’d have to get back on the road, then opine about the unbelievable gas prices. Just the two of them, they’d play off each other better—even happier—without me to complicate the birth order. My sister would shine in the absence of my shadow, empowered to connect and laugh off others’ chagrins. And my brother…well, however he was, he’d still be alive.

Then, my partner—whose charms I’ve devoted sonnets to—would want for not, whether he was alone on the sidelines, gauging his pride in observing the lack of others’; or bemused by some bombshell. I’d encounter him near campus. I’d blush when he’d answer the door, just as he did the day we met. But this time around, I’d be less stiff and proffer more insight to our conversation. Since his specialties are in science and mine are humanities, I’d admit to reaching across the aisle every so often because I was fascinated by generative adversarial networks and causal loops—until it’d occur to me that I was rambling, but he was politely listening all the same. Then, I’d think of us together elsewhere, somewhere else in time; where neither of us would think twice to declare our truths. And I’d feel like crying, albeit I’d be consoled by the time at hand wherein my non-existence is for the best.

And in all these encounters, if I ever found myself entreated by one of these people I care for, my answer would never change: “No thanks. Maybe some other time.”

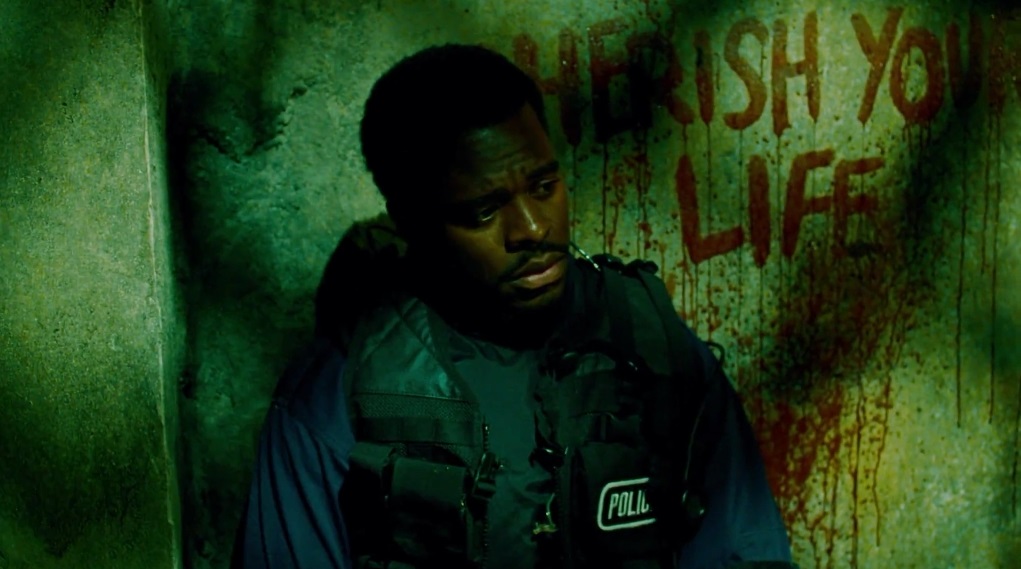

This kind of rising action isn’t exactly new, but precarity is what marks this departure: how easily havoc can be wrought by ranks and media is what’s thematic of the overall film. I found Truth or Die more honest and grounded than similar series—

This kind of rising action isn’t exactly new, but precarity is what marks this departure: how easily havoc can be wrought by ranks and media is what’s thematic of the overall film. I found Truth or Die more honest and grounded than similar series—

Fame is not unlike writing. It’s about quantity, not quality. Writers are seldom seen for their words, but their assets. Calling myself a writer inclines folks to ask not what I write, but what I’ve sold; and since I’m not really selling—at least, under my name—I don’t have any business calling myself one. The only things I have to show for my writing are a fat stack of manuscripts—novels, short stories, screenplays, an unfinished memoir—rivaled by an even thicker packet of rejection letters. A stray reader may leave a decent review. They have hope I can either improve or publish something to acclaim.

Fame is not unlike writing. It’s about quantity, not quality. Writers are seldom seen for their words, but their assets. Calling myself a writer inclines folks to ask not what I write, but what I’ve sold; and since I’m not really selling—at least, under my name—I don’t have any business calling myself one. The only things I have to show for my writing are a fat stack of manuscripts—novels, short stories, screenplays, an unfinished memoir—rivaled by an even thicker packet of rejection letters. A stray reader may leave a decent review. They have hope I can either improve or publish something to acclaim.